Our in-house Sustainability Strategist Michelle Xuereb shares her thoughts on making our buildings resilient to our changing Toronto climate.

Traditionally, sustainable building design has focused on doing less harm through mitigation. But our changing climate and extreme weather events around the world are prompting a new dialogue. Cities of the future will have to create built forms and strong communities of people that are able to adapt, respond, and recover from extreme weather events if they want to attract investment and talent – we are seeing a shift in focus from harm reduction to strategies of minimizing down-time and returning quickly to “business as usual”.

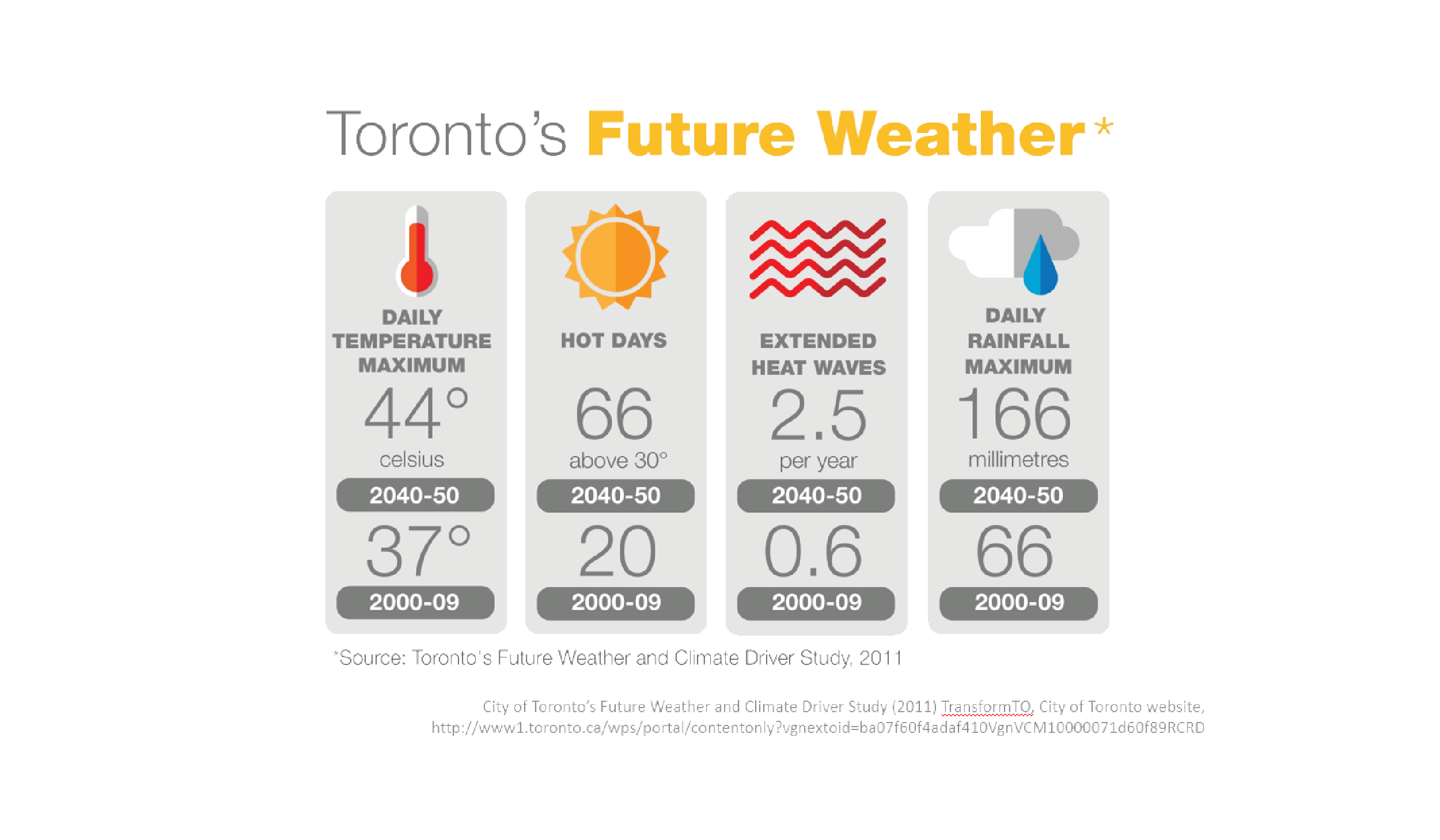

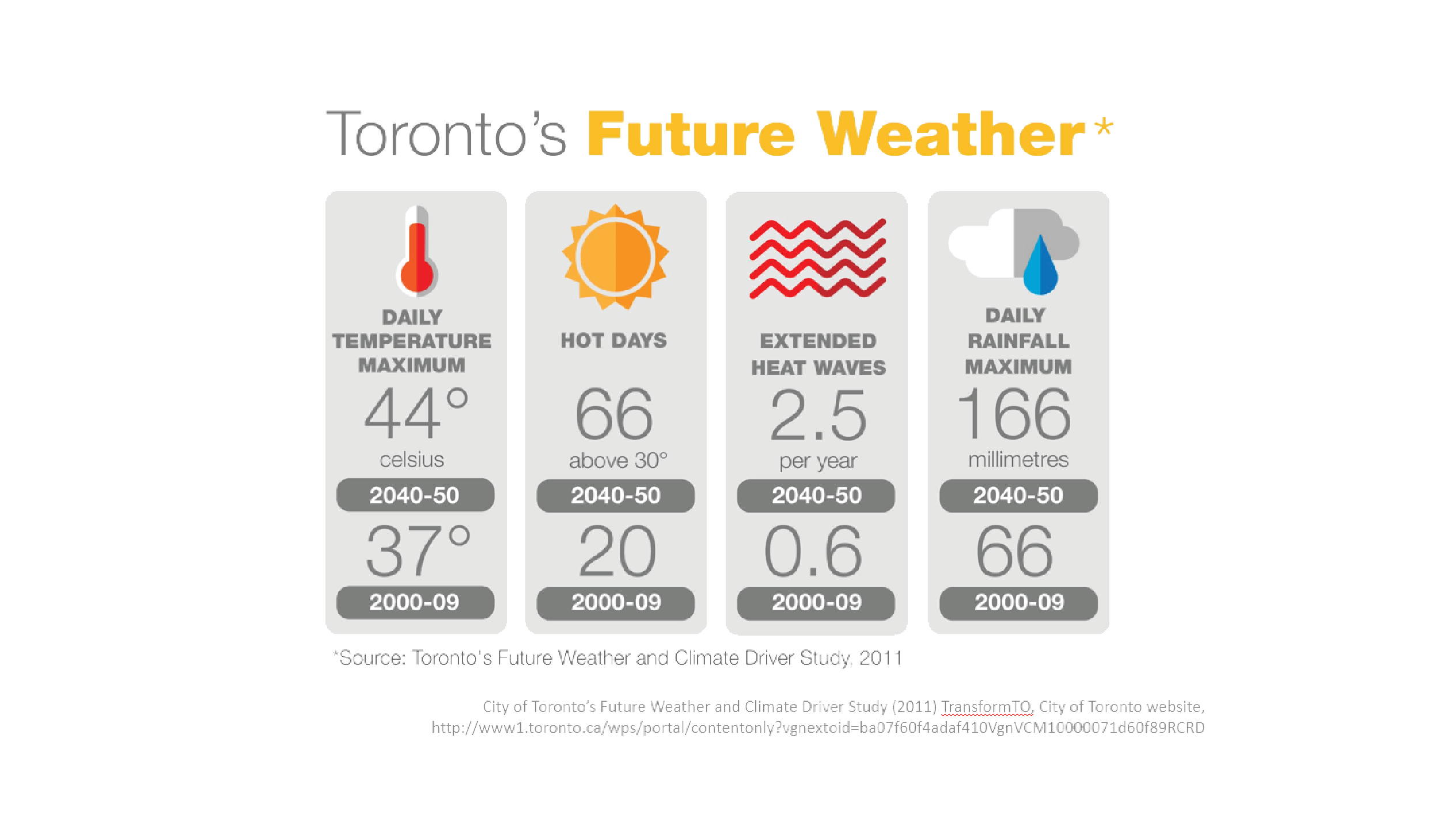

The first step to creating more resilient buildings is to know the local risks. In 2011, The City of Toronto commissioned a report on The City of Toronto's Future Weather and Climate Driver Study. The forecast for 2050? Hotter days, and more of them, lasting for extended periods of time, and an increase in the amount of precipitation during single storm events.

We’ve already experienced the flooding of the Toronto Islands in 2017, the ice storms in winter 2013 and the summer flooding of that same year - all came in tandem with large scale power outages. These power outages can bring business to a grinding halt, close transit systems, strand people in high-rise structures and leave people without heating/cooling or power, sometimes for several days.

Carp took over the Gibraltar Point Baseball Park on the Toronto Islands during the spring flooding of 2017. (Credit: Bernard Weil / Toronto Star)

What we have to think about, then, is the concept of sheltering in place.

Think back to the images that came out of Florida and Texas after the severe flooding this past fall- highways backed up and gas stations emptying out. Everyone was leaving and, in the process, stressing the infrastructure. This is what horizontal evacuation looks like. Just imagine how different the situation could have been had those places been designed so that people could remain safe without relocation.

Traditional building codes are designed to minimize the spread of fire and to maintain life safety systems long enough to allow the safe evacuation of its occupants. The danger is considered to be a single acute event that requires occupants to evacuate immediately. During an extreme weather event, the timelines are generally prolonged as first responders work to bring major infrastructure back on line and tend to emergencies. The key function of buildings at this time is to provide shelter. One way we can measure a building’s ability to do this successfully is look at its passive survivability.

Our current codes, however, do not require critical life safety systems to function for extended periods of time without power, fuel or water. There are currently no building codes that require us to discuss or integrate the concept of a building’s passive survivability into building design, which may leave a community unable to use it for sheltering in place during these times.

So, what should we be talking about? In Toronto, we should be considering how to keep key infrastructure dry in the event of extreme rainfall, warm in extreme cold, and cool in extreme heat – all assuming no power, fuel or water for a minimum of 72 hours.

Extreme rainfall can cause our waterways to overflow, resulting in sewer and storm systems backing up into our streets and buildings. Determining whether a potential property sits in a flood-prone area is a key step in land acquisition. It could be the difference between being able to secure insurance for your property or not. Providing this information to your designer can provide clues as to where your key infrastructure, such as the back-up generator or the transformer, should be located. Traditionally these rooms are located in the underground parking levels – areas which have the lowest real estate value. Considering the life cycle cost to replace a unit damaged by flood, the potential claims by tenants for down-times to their businesses and the amount of acute effort to deal with an emergency situation, locating these rooms above the flood line can make more sense.

For existing buildings this may not be feasible, but there are still things you can do to mitigate water damage, such as installing backflow preventers, raising the height of electrical outlets and/or using mould resistant materials below the flood line. Knowing that an area is subject to flooding changes the way you think about designing it.

One suggested practice is to create an “area of refuge” (min. 93sm or 0.5sm/resident) with separate 72-hour back-up power dedicated to providing lighting, heating/cooling, ventilation and water pumps to the area. The area of refuge is a place where people can go to warm up/cool down, charge communication devices, keep critical medications cool, and organize themselves during extreme events, enabling residents to shelter in place while the city works to restore infrastructure.

In terms of managing temperature during extreme heat or cold, prioritize design decisions which increase a building’s thermal resilience. Highly insulated walls maintain more consistent temperatures in the event of a power outage. Following passive design principles is a good strategy. Consider orientation since buildings tend to overheat on the west and south, and reduce the window to wall ratio by using walls, not window walls. Provide the best possible building envelope that the budget can afford. Minimize thermal bridging. Locate balconies on the south to provide passive shade. Locate operable windows in all rooms to promote natural cross ventilation. All of these factors can enable a building to maintain its temperature.

Finally, the demographics and rapid population growth in Toronto should be taken into consideration. We are growing at an extremely fast rate, with over 500 proposed developments in the pipeline - that’s a lot of new neighbours who don’t know each other. The reality is that it’s your immediate neighbours who can help in an emergency and we need to create opportunities for social connection in our towering residential communities so that people know to look in on seniors who live alone or those who may need medication. As designers we can create complete communities where building residents can get to know one another by spreading amenities throughout the towers and creating shared spaces like stairwells that are actually desirable to use.

Things are already changing. The City of Toronto was selected to be part of 100 Resilient Cities, an organization started by the Rockefeller Centre and dedicated to helping cities grow their physical, social and economic resilience. Additionally, the new Toronto Green Standard Version 3.0 coming into effect in May 2018 will foster this discussion. This new standard will mandate that new Toronto projects meet higher energy performance requirements to increase the thermal resilience of our new building stock. Projects targeting Tier Two will be required to meet multiple absolute performance targets, set intentionally to reduce carbon emissions and prioritize building envelope strategies. As part of a Tier Two submission, proponents will be required to complete a Resiliency Checklist, which includes questions about design weather files used for energy modelling, the extent of back-up power generation provided, and flood mitigation strategies incorporated into the design.

So, what can we do to future-proof our buildings?

- Understand local climate change risks and adaptability strategies;

- Demand that passive design solutions to reduce thermal demand, mitigate flood and anticipate power outages be prioritized;

- Request the use of climate future scenarios during the design process for new building design and test future weather scenarios in existing assets;

- Prioritize designs that support social connection and ambitious change.

Solutions exist, we just have to start the conversation.

For more information on Michelle’s role as Sustainability Strategist at Quadrangle, click here.